Children learn to interact with others by imitating their peers, particularly those who share similar characteristic, such as age or gender. Even fictive models are efficient. Role models can convince an individual that their abilities are limited. This is known as the “stereotype threat” and it has been experimentally observed. When it comes to gender prejudices, the effect of prejudices can be reduced when children learn that any competence can be developed, and that sex is determined by the genitals, instead of clothing or attitudes.

Observation and imitation

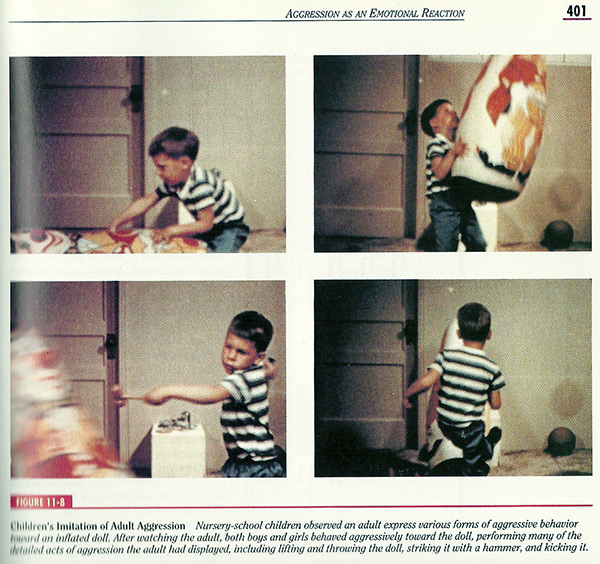

An individual and especially a child can model his behaviors through imitation (copying a model) and observation (general rules across multiple models) of people who belong to the same reference group. Observation and imitation can be considered as powerful agents of cultural transmissions.

Imitation is particularly done on a reference group (group the person belongs to, or wants to belong to). Children and teens discover values and behaviors of their peers through family, school and media. Perception of the peers group is built around individuals who are used as a reference to define the group (Zavalloni, 1984, 1986).

Source : “Hilgard’s introduction to psychology”, 1996, Rita L. & Richard C. Atkinson, Edward E. Smith, Daryl J. Bem, Susan Nolen-Hoeksema

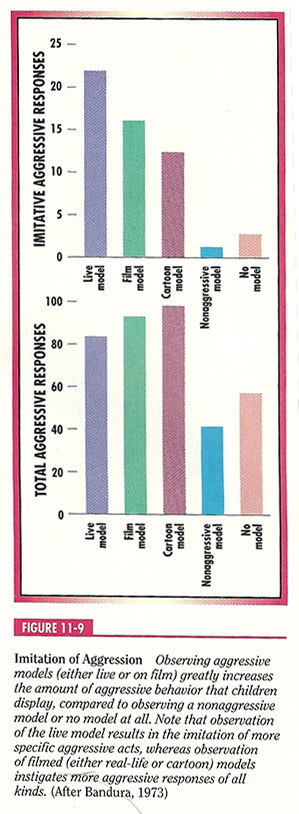

According to Cordua, Mac Graw & Drabman, 1979, models are more effective if they belong to real life rather than media. However, Bandura, in 1973, notes that observation of the aggressiveness of live model results in the imitation of more specific aggressive acts, whereas observation of filmed models (either real-life or cartoons) instigates more aggressive responses of all kinds.

Source : “Hilgard’s introduction to psychology”, 1996, Rita L. & Richard C. Atkinson, Edward E. Smith, Daryl J. Bem Susan Nolen-Hoeksema.

Pygmalion effect and Stereotype threat

A study by Frederique Autin, Fabrizio Butera and Anatolia Batruch, in 2018, shows that the image that teachers have of a student influences their rating. Their rating is worse for the same copy when they believe that the student comes from a disadvantaged background.

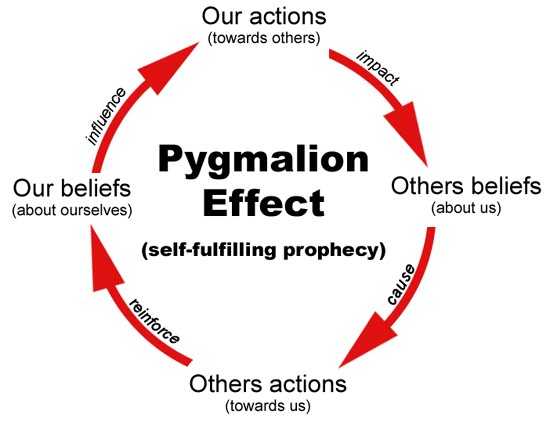

Even more frightening, the image that the adult has of the child changes the child’s self-image. This effect was experimentally demonstrated by the Rosenthal brothers in 1968, who call it the Pygmalion effect.

Rosenthal brothers tested children’s IQ in school and gave fake results to the teachers at the beginning of the school year. During the year, the students who were presented as “good” had better average results at school than others. A new test of these “pretended” good students showed an increase in their IQ. Students for which no positive expectations have been induced are described as less curious, less interested, less happy, and having less chance of success in life.

Since only the teachers knew the results of IQ tests, only their attitude towards the students can explain this result. Rosenthal brothers do not observe precisely the mechanisms at work in the transmission of the prejudices of the teacher to the students. Has the student been less questioned, less listened to, more criticized? When did the image of the student’s teacher become the student’s self-image? How does self-image affect performance?

Source: https://sites.google.com/site/7arosenthal/

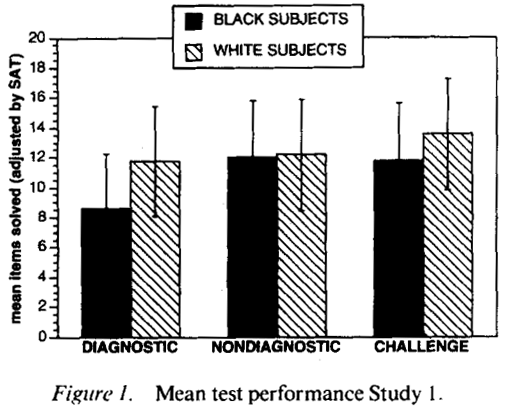

A research conducted by Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson can answer to this last question.

In an article published in 1995 in “Journal of personality and social psychology”, they show that black American perform worse than white American on an verbal test (SAT) if they are told beforehand that this test will diagnose their intellectual ability. There is no significant difference in performance if the test is presented as a laboratory problem-solving task that was non diagnostic of ability. There was a third condition in which the test was presented as challenge, although non diagnostic of ability, for which results were in between. They did other experiments showing that black Americans had more anxiety, doubts about themselves and prejudices when the test is supposed to measure their intellectual abilities.

Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson conclude that the anxiety about the threat of an intellectual diagnosis and even a challenge, is due to black Americans’ prejudice about their ability, and that their lack of self-confidence impairs their performance. They call this effect the “Stereotype threat“.

Claude Steele & Joshua Aronson, 1995

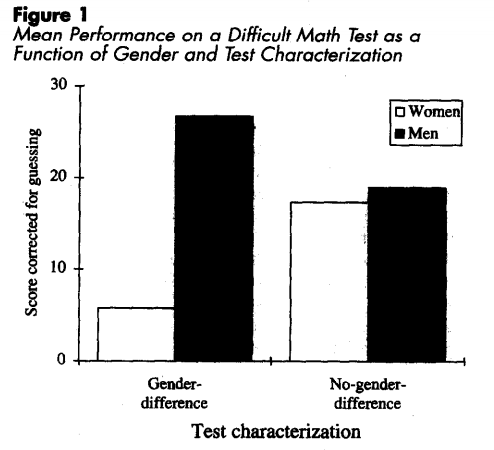

Another article published in 1997 in the journal “American Psychologist” by Claude Steel shows a similar phenomenon between men and women. Women are less successful than men in a difficult math test if they are informed in advance that the test generally shows gender differences, while there is no significant difference between participants if they are told that men and women perform as well on this task. Other experiences also found that participants’ post treatment anxiety, not their expectancy or efficacy, predicted their performance.

In the ensuing decade more than 300 studies have been published that support this finding.

The results of these experiments show that stereotype threat is often the default situation in testing environments. The threat can be easily induced by asking students to indicate their gender before a test or simply having a larger ratio of men to women in a testing situation (Inzlicht & Ben-Zeev, 2000). Research consistently finds that stereotype threat adversely affects women’s math performance to a modest degree (Nguyen & Ryan, 2008) and may account for as much as 20 points on the math portion of the SAT (Walton & Spencer, 2009).

Aronson’s research also has shown that high-achieving and motivated women in the pipeline to STEM majors and careers are susceptible to stereotype threat.

In France, Pascal Huguet (CNRS) and Isabelle Regner (Toulouse University) present a test to teenagers. If it’s presented as an exercise of geometry, there is a large gaps between the performances of boys and girls. There is no difference in performance between boys and girls if the geometry test is presented as an exercise of drawing.

This experiment also illustrates the negative impact of stereotypes on girls: the performance gets worse on the same task when they think it’s about math, because they do not believe in their skills in mathematics.

Carol Dweck, social and developmental psychologist at Stanford University, provides evidence that a “growth mindset” (viewing intelligence as a changeable, malleable attribute that can be developed through effort) as opposed to a “fixed mindset” (viewing intelligence as an inborn, uncontrollable trait) leads to greater persistence in the face of adversity and ultimately success in any realm.

People with a “fixed mindset” tend to avoid challenges, give up easily, see effort as fruitless, ignore useful negative feedback and feel threatened by the success of others. Whereas people with a “growth mindset” embrace challenges, persist in the face of setbacks, see effort as the path to mastery, learn from criticism and find lessons and aspiration in the success of others. As a result, they reach ever-higher levels of achievements.

When it comes to gender prejudices, many studies show that a growth mindset protects girls and women from the influence of the stereotype that girls are not as good as boys at math.

Dweck and others have found gender gaps favoring boys in math and science performance among junior high and college students with fixed mindsets, while finding no gender gaps among their peers who have a growth mindset (Good & al., 2003; Grant & Dweck, 2003; Dweck, 2006).

Dweck and her colleagues conducted a study in 2005 in which one group of adolescents was taught that great math thinkers had a lot of innate ability and natural talent (a fixed-mindset message), while another group was taught that great math thinkers were profoundly interested in and committed to math and worked hard to make their contributions (a growth-mindset message). On a subsequent challenging math test, the girls who had received the fixed mindset message and the stereotype of women under performing in math, did significantly worse than their male counterparts; however, no gender difference occurred among the students who had received the growth-mindset message, even when the stereotype about girls was mentioned before the test (Good & al., 2009).

Stevenson & Stigler (1992) note that, in cultures that produce a large number of math and science graduates, especially women, including South and East Asian cultures, the basis of success is generally attributed less to inherent ability and more to effort.

All this is very interesting, may we think, but in the end, aren’t there still some “natural” differences in the intelligence of men and women? After all, the greatest geniuses are all men, aren’t they?

Well, no ! Simply, female geniuses are less known, less visible, and sometimes despoiled. I invite you to discover some of them on my other website: go-women.com

Natural vs cultural image of gender

It is interesting to describe, about the construction of identity through imitation, a study conducted by Sandra and Daryl Bem (1996). They find that children who have a biological definition of gender also have a more stable sense of their gender, because they are not afraid of losing their masculinity or femininity if they have a behavior that is atypical for their gender. Such children should then be less stereotyped in their behavior, more able to resist social influences and pressures that are trying to force them into stereotyped behaviors, and more tolerant of people who do not conform to stereotypes. However, children who identify sex with cultural indicators, like hairstyle and clothes, should have more tendency to be more gender stereotyped.

This idea is confirmed by a study conducted on children of 27 months. They are asked to identify the sex of the people in a brochure, who have conventional clothes for their gender. Children who answer correctly (about half of them), are called “early labelers”. Observation of these children shows that they spend twice more time than others on gender stereotyped toys. Additionally their father defends, more than other children’s father, the idea that boys and girls should have different toys, that they should not see a person of the opposite sex naked, and that they should not have sexual information. They also have more tendencies to avoid their children’s questions about sex and they express more traditional opinions about women. These differences not observed in mothers (Fagot and Leinbach, 1989). These results are consistent with other studies (see “Active learning“), which show that father are more concerned than mothers about gender-stereotyped behavior in their children.

Sandra and Daryl Bem conclude that teaching children early that the genitals determine the sexual gender, should immunize them against an unconditional acceptance of gender roles.

The difference between children educated with and without an organic definition of gender is illustrated by Sandra and Daryl Bem’s own son, Jeremy. He decided one day to wear barrette in preschool. Another boy told him that only girls wear barrette. After he talked with his parents, Jeremy said to the other boy that wearing barrette does nothing, being a boy means having a penis and testicles. The second boy responds then “everyone has a penis, only girls wear barrette”.

It would be interesting to follow the gender development of children who have been on naturist campsites. I have, and, I don’t know if it is related, but, until I’ve been a teenager and started to feel pressured by peers, I was never concerned about proving my sex through my clothes and my behavior.

Is nudity sexual?

If we let children go naked, for example, in the context of vacations, what about adults? Should they be naked like children, so that they know it’s not different? But, isn’t it likely to degenerate into sexual harassment?

In fact, it is clothing that sexualizes nudity, because the only people of the opposite sex that we see naked are those with whom we have sex, or those who are seen in the media in erotic staging. Among hunter-gatherers, nudity is common, without arousing sexual desires. Animals and plants are naked, there is nothing sexual about it. The border between the “decent” and the “indecent” (what is sexual or not), depends precisely on the amount of clothing that one is accustomed to see on others.