Coactive learning is a way of learning by interaction with others. This is an efficient form of learning and co-working, if the group is given good conditions to work together. Otherwise, group activities can result in the affirmation of the most aggressive people, and in the reduction of self-confidence and withdrawal of some others. There are various factors involved in the effectiveness of coactive learning. We will see the influence of the spatial arrangement, of the nature of the task, of the leadership, then how we can improve empathy. Finally we will study collective polarization and rumors.

Spatial arrangement

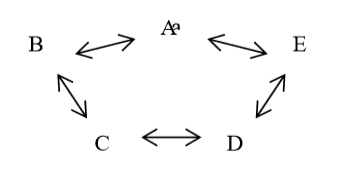

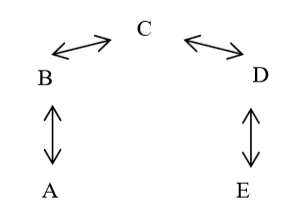

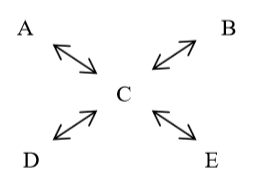

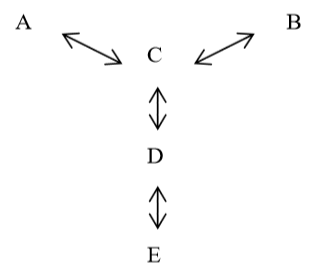

Leavitt (1951) proposes a collective task with 5 subjects: finding the missing figures on 5 cards of 5 figures, knowing that each subject has a card with a different missing figure and that it is necessary to reach 5 identical cards. Each subject passes one card at a time by another subject. Leavitt varies the disposition of the members of the group: in circle, in chain, in wheel or in Y.

And it measures the number of exchanges of information and the satisfaction of the members.

The results show that centralized structures (wheel and Y) are more efficient than decentralized structures (circle and chain): they require less information exchange to reach the solution, but the only satisfied members are those who are at the center of exchanges (D and especially C), felt by others as leaders, because they are the ones who direct the flow of information. Decentralized structures produce a more balanced satisfaction among the members of the group but are slower to solve the problem.

Nature of the task

Faucheux and Moscovici add a factor to Leavitt’s experience: the nature of the task, and propose two types of collective tasks:

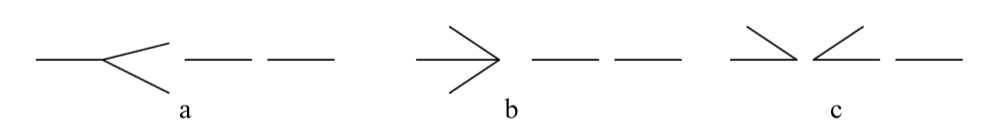

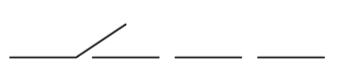

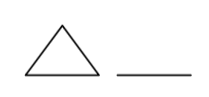

– a task of creativity (the Riguet tree): it is to obtain the most different figures of figures a, b, c, from an initial figure, closed figures being excluded.

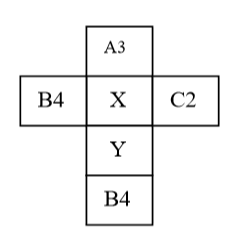

– a problem solving task (Euler’s figure): replacing the boxes X and Y by a letter between A and D and a digit between 1 and 4, without repeating, in a same row or column, a number or a letter, and without using A1, B2, C3 or D4.

Results show that the decentralized structures are more efficient for the task of creativity while centralized structures are more efficient for the task of problem solving. Moreover, they observe that if the group is allowed to structure itself, it spontaneously takes the most effective disposition in relation to the nature of the task.

Leadership

To study the effect of the the style of leadership in a group, Lipitt and White propose to 3 groups of children the construction of the stage set of a theater, with a group leader. Each week a different style of leadership is applied:

– Authoritarian Leadership: The adult makes all decisions about activities, assigning tasks and does not reveal anything in advance. He stays away from the group for anything that is not directly related to the task.

– Democratic leadership: the decisions to be made are submitted to the group that discusses them with the participation of the adult. As soon as children stumble over a technical problem, the adult tries to provide at least two alternatives. Every child is free to work with whoever he wants.

– “laissez-faire” leadership: the adult gives the children total freedom of activity and organization. It merely repeats the instruction, indicates the available equipment and only gives help when a child asks for it. In no case does he evaluate positively or negatively, but he tries to be friendly rather than distant.

The results reveal a maximum efficiency for the democratic group, then the authoritarian group. The laissez-faire group is very unproductive. These results are consistent with those obtained with respect to the effectiveness of a decentralized structure for a creative task. In addition, when the facilitator is absent, the democratic and laissez-faire groups continue their activity while the authoritarian group stops.

The measure of aggressiveness within the groups shows that an authoritarian leadership produces intergroup aggressiveness, whereas not having a leadership maximizes aggressiveness within the group. The democratic leadership annihilates all aggressiveness, as children are fully focused on the creative activity.

Nowadays, French schools are on the “Laissez-faire” leadership style (which means, no leadership at all). Many governments who’ve unsuccessfully tried democracy were in fact also failing in developping a democratic leadership (having corruption instead), and fell into an authoritarian (religious) one because of the damages caused by full freedom of people (“Laissez-faire”), giving rise to the law of the strongest. I suspect this will also be the fate of the western world.

Learning empathy

To work better together in a democratic way, it is essential to understand each others, so to cultivate empathy, that is, the ability to identify oneself with the other and to understand and anticipate one’s ideas and emotions.

Many exercises can be done by adults as well as children to cultivate empathy.

Ashoka proposes a toolkit for schools and families. The exercises are grouped in 3 steps:

– prepare (at the beginning of the year for a school): creating a safe space for the participants

– engage: group play, storytelling, and collective problem solving

– reflect & act: participants identify shared values and differences, and instill courage courage to enable action

Here are some examples of activities from this document:

– Sample exercise of the “Prepare” step: break students into small groups of 3 or 4 to brainstorm and decide upon a set of words that answer this question: How do you want to feel in the classroom each day? Collect the words from each group, listing them on the board. Discuss as a whole class which words are the most common and give students the opportunity to advocate for a particular word. Students vote on their favorite three words, and the five words (or more) with the most votes will form the foundation of the charter. Another step is to work with the students to turn feelings into rules and expectations. For example, what does “respect” look like in everyday practice? Be as specific as possible: Rather than landing on “being nice,” encourage them to identify specific behaviors that they can track and hold themselves accountable for. For example, taking turns speaking, making eye contact, sitting up, etc.

– Sample exercise of the “Engage” step: either read a story, a chapter of a history book or an article in the newspaper, or watch a documentary. Then ask the students to answer the following questions:

How would you feel if you were [person/character]?

How do you think [person/character] might be feeling? How do you know?

Can you think of a time when you felt the same way?

What led him/her to make that (pick one) choice?

What would you have done differently in that situation?

Which character in the story do you relate to most and why?

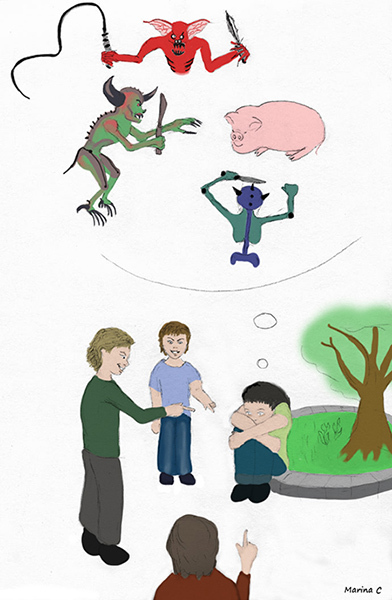

– Sample exercise of the “Reflect and act” Step: begin by asking students, “Have you ever seen or heard someone being bullied or called a name? If so, how did it feel?” Start them off by sharing your own experience. Then ask students to share their answers one at a time, when they’re ready. Afterward, brainstorm what students can say or do when they witness name-calling or bullying, recording each suggestion on chart paper. Introduce the concept of a safe response, such as: say what you feel, take a stand by using words or phrases that interrupt or end the name-calling, ask for help from an adult, find a friend, ignore the situation or exit the area…

When it comes to mobbing, my personal experience has taught me that the highest risk for a child is to be isolated.

An isolated child is a child in danger.

There are also interesting exercises used in acting. For example :

– Each member of the group, in turn, performs for one or two minutes, slow movements that the others imitate.

– Form a circle, holding hands, and “to pass a stream” by tightening the hand in the direction opposite to that which one receives. The person who emitted the current first can emit another later in the opposite direction.

– One person speaks and another, behind her, makes hands, having significant gesture according to the speech or manias (ex: scratching the chin or hair).

– Guide another person who has a blindfold, then reverse the roles.

– In a circle, one after another completes the words of the others to make a sentence (verb, adjective, nominal group, etc., but no “little words” such as “the”, “of”, etc.)

– improvise a scene on a subject, for example: a girl comes home very late and her parents express their concern.

Collective polarization

In the 1950s, people use to think that decisions made by groups moderated individual decisions. James Stoner (1961), a student in management in the U.S.A., decided to test this assumption. He questions people about various dilemmas, individually, in groups, and again individually. For example, an engineer must decide between keeping his current job with a modest but correct salary and with confidence on the stability of the company, or take a new high-paid position in a company that has just been created, and that has not yet proved its viability. The subjects make their decision on a scale of chances, in our example of the engineer, will he change position knowing that the chances of success are 5 out of 10, 3 out of 10 or 1 in 10. When Stoner compares group decisions with decisions taken before by the same individuals, he observes an increase in risk taking, this new opinion remaining stable in a second individual measure.

Other results show that the group decision can result in a decrease in risk taking compared to individual decisions.

Collective decisions tend to accentuate the initial positions of the members of the group.

This effect is called “collective polarization”. Several explanations have been proposed. Here are the two main ones:

– The informative influence: the members of the group learn new information and hear new arguments but they tend to raise more arguments in favor of their initial position than against. They thus skew the discussion and push the final decision further in the direction of the initial positions.

– Normative influence: people compare their own initial point of view with the group norm. They can thus adjust their position to comply with the position of the majority. The group provides a canvas of references that makes its members perceive their initial position as too weak or too moderate.

Other studies show that the personal involvement of group members increases collective polarization, and that the initial position of a directive leader polarizes the group towards his decision.

To show this phenomenon, Janis (1982) establishes a historical study on three American failures:

– The Pearl Harbor Affair (1941): The military in place had warned the U.S.A. headquarters of a possible attack by the Japanese air force, but the information was ignored.

– The Korean War (1950): The Americans had planned to invade Communist North Korea, but the Chinese intervention had been underestimated.

– The landing in Bay of Pigs (1961): the American strategy did not take into account the roughness of the terrain (presence of mountains, for example).

This study shows that the failures were all due to a collective polarization during the discussions in military or governmental councils, towards the initial positions of a too directive leader. This does not mean that the presence of a leader is harmful, but that he/she must be trained in group dynamics. She/he must be able to encourage participation, contradictory arguments and their dialectical resolutions, the diversification of points of view, and to put mutual respect into practice. He/she does not take a stand before the discussion begins. Janis also prescribes the renewal of meetings (to allow time for individual reflection and a second chance to alternatives), the presence of people having an opposite opinion and experts, to temper the phenomenon of polarization.

The process and damages of rumors

Rumors are a dangerous phenomenon of collective polarization. They are particularly involved in the designation of scapegoats. They can also influence testimonies, members of a jury, therefore decisions of justice, political or military actions …

They were studied by psycho-sociologists Allport and Postman (1945). During the Vietnam War, a rumor spread about disproportionate damage caused by the failure of Pearl Harbor. Although Roosevelt denied this interpretation, a survey of students before and after the speech reveals that anxiety continued. To understand this phenomenon (the birth and persistence of rumors), they analyze 1000 types of rumors collected in 1942. They find that within a group, the spread of rumors about a specific subject is directly related to the importance and the ambiguous nature of this subject for the life of each member of the group. The content of the rumors is generally hostile (60% of the 1000 rumors studied) or express a fear (25%).

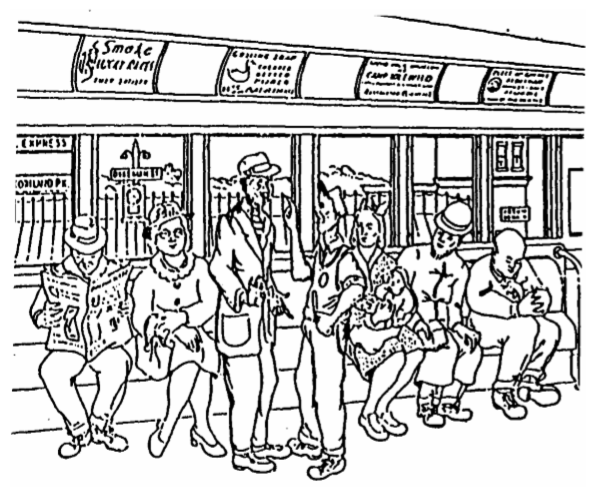

Allport and Postman perform an experiment on 40 groups of subjects to analyze the cognitive processes at work in the propagation of rumors. In each group, 6 or 7 subjects volunteer to go out while the rest of the subjects watch an image.

A subject enters and sees the image, then it is removed and a second subject comes back to listen to the description of the image by the first subject. The other subjects return one by one to listen to the description transmitted by the last one having heard it. The analysis of speech transformation shows the following processes:

– reduction: the message tends to be simplified and shortened.

– accentuation: the message is transmitted by selecting and exaggerating certain details.

– assimilation: the content of the message reflects the habits, interests and feelings of the transmitters.

Collective memory performs, in a few minutes, a reduction equivalent to that achieved by an individual memory in a few weeks.

The structure of the message adapts, on the one hand to the human cognitive functioning, on the other hand to individual and cultural representations.

The intervention of the laws of the cognitive functioning appears in the following effects:

– the consistency of messages or their assimilation to a main theme, such as the texts recalled by Bartlett’s subjects: if in the picture, a Red Cross truck appears loaded with explosives, it is described as carrying medical equipment.

– the need to retain a spatial-temporal structure: the first sentence places the message, “this is a battle scene” for example.

– a better retention of familiar and significant symbols: in some images, the church and the cross.

– the addition of explanations: “an accident occurred”.

Social representations and their emotional charges appear, for example, in the description of black people: the knife goes from the hand of the white man to the one of the black man, the number of black people is accentuated …

Allport and Postman conclude: “We will speak of the triple process of transformation (reduction, accentuation, assimilation) of a rumor, as a process of consolidation. It is clear from all our experiences, as well as from other researches carried out in this field, that all subjects face the difficulty of grasping and retaining, in their objectivity, the stimuli coming from the outside world. To be able to use them, they must restructure them in order to adjust them to their boundaries of comprehension and memory, on one hand, and to their personal interests and needs, of the other hand. What was external becomes internal, what was objective becomes subjective. The kernel of objective information received by the individual is so deeply integrated into the dynamic of his mental life that the transmission of a rumor is mostly a projection mechanism.”