We learn primarly by building asociations over basic needs. This process is called conditioning. More complexe associations such as symbols, occur later. Stages of child development have been studied by Piaget. In this development, the action of the child on the environment plays en central role.

Conditioning

Classical conditioning is the learning of an association between two stimuli. Operant conditioning is learning of an association between a stimulus and a behavioral response.

Classical conditioning – learning a relation between stimuli

Classical conditioning was described by Pavlov in the beginning of the last century, with researches on dogs: a neutral stimulus, like the sound of a bell, triggers the dog’s attention, or “orientation response”. If the tone is associated with an unconditioned stimulus, food, that provokes an unconditioned response, salivation, after a few times the tone is enough to provoke the salivation. The tone becomes a conditioned stimulus and the salivation becomes a conditioned response also called “conditioned reflex”.

Classical conditioning creates a perception of the world: stimulus of our environment, that are not ignored by habituation (see below), evokes associations with emotions (pleasure, fear, anger…) and appropriate behaviors (approach, avoidance, aggression…), and the relationship between stimulus and our primitive needs is indirect and constructed.

Operant conditioning – learning relation between a stimulus and a behavioral response

Also based on an association of stimulus-response, it’s the person’s behavior that induces appearance of a desired target (or the disappearance of something unpleasant).

These associations are enhanced by repetition. A behavior can also be inhibited by punishment or no reward. A reward seems to be more effective when it is of a social nature (compliments, smiling, esteem, love …).

Operant conditioning models the impact one has on its environment. For example, being successful on a task at school as a result of a hard work, causes the student to maintain or increase this hard work. Congratulation and esteem from other children when a child hits another, encourages him to repeat the same behavior, while he is discouraged in an environment of children who hate violence and exclude him for such behaviors.

In all forms of conditionings, the withdrawal of a conditioned stimulus produces an extinction of the conditioned response.

Stimuli that act as reinforcements, are in the beginning “primary” and common to all individuals, and become more and more deferred: they are reached through indirect reinforcements, special to the history of an individual, social group or culture. For example, money is an indirect reinforcement, as it allows the satisfaction of other needs.

Relationships between stimulus-responses can be generalized to similar stimulus or stimuli that occur simultaneously. They can, on the contrary, be made more specialized, if only one component of a stimulus continues to bring reward or punishment, since similar stimulus that don’t have this component don’t trigger the same event.

Associations become more and more sophisticated, and perceptions and behaviors resulting from previous associations prepares future associations, as a network that develops and stays open.

One question that one can have when reading about behaviorism, what are the primitive needs on which are based all associations?

Studies on motivation suggests some theories on basic needs:

– Physiological needs: experiments on animals in behavioral researchs often uses hunger and pain.

– Social needs: attachment (Bowlby), tenderness (Harlow), affiliation (resulting from “imprinting” described by Konrad Lorenz).

– Cognitive needs: exploration (Butler), manipulation (Harlow), and curiosity that, according to Berlyne, consists of a need for novelty, incongruity, complexity, and conflict.

Habituation and sensitization

Habituation

We are permanently exposed to a large quantity of information. So, to maintain a cognitive stability (or respect the cognitive development speed), one must be able to discriminate the appropriate stimulus from the constant “background noise” of the environment

Habituation does this: to repeat a stimulus without any kind of reward leads first to a reaction of curiosity (watch the stimulus for example) to more and more indifference, until the stimulus is completely ignored.

Habituation differs from physical fatigue or sensory adaptation because it is a specific response to a stimulus. As conditioned responses, habituation can be generalized or specified, to/from stimulus that have common characteristics.

Habituation can also be switched off:

– If a new stimulus is happening almost simultaneously with others that the subject has been accustomed to.

– If there is a long time before the stimulus happens again.

Habituation is a powerful tool to keep crowd’s inertia. It is used by governments to make people accept unpopular measures (increase in taxes, reduction of compensation …)

Similarly, the degrading image of women in fictions (presented as less intelligent, less courageous than men), repeated systematically, trigger no attention, they become unconscious, therefore their influences over our judgment is difficult to identify and to control.

Sensitization

Sensitization also occurs through the presentation of an attractive stimulus, often enough to be rembered, not often enough to causes habituation.

Sensitization explains how advertising works: a need is created by the display of a product and its benefits. The need can only be satisfied by purchasing the product.

Complex associations

As associations become more complex, generalities emerge. They will base the abstract reasoning, which is accompanied or not by symbols.

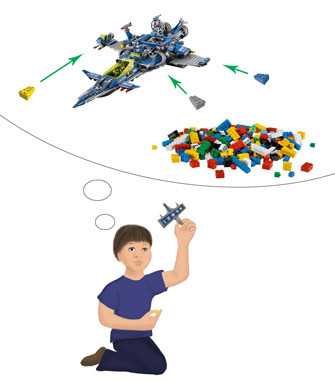

According to constructivist theories founded by Jean Piaget, it is the action of the child on his/her environment that will lead her or him to build an increasingly abstract knowledge. By focusing on the child’s action, Piaget implicitly address a critique of the academic way of sharing knowledge, at least for youngest children.

Learning should start from the concrete to the abstract and let the child manipulate objects related to the concepts that she or he has to learn.

This conception of learning had already been formulated a few years earlier by Maria Montessori.

Piaget’s observations of children at different ages allowed him to define the following phases (I use the feminine form to avoid overloading the text of “she/he” or “he/she”):

– From 0 to 2 years old, the child is in the sensorimotor phase: she learns by trial and error the relation between what she does and what she feels (a relation also described above in “operant conditioning”). At the end of this stage, she is aware of “the permanence of the object”: the object continues to exist even if she does not perceive it anymore.

Example: When hiding a toy under a cloth, the 8-month-old baby stops watching it. When a little older, she lifts the clothes to find the toy.

– From 2 to 6-7 years, the child is in the preoperative phase: she learns to speak, so to associate things with symbols. She gradually learns the notions of quantity, space, time, but remains essentially anchored in the immediate experience. She does not see other people point of view as different from hers.

Example: When a 4-year-old child sees the same amount of water poured into vases of different shapes, she says there is more water where she sees the highest water level.

– From 6-7 years old to 11-12 years old, this is the phase of concrete operations: the child is able to learn mathematics. But logical reasoning remains in relation to the concrete.

Compared to the previous example, the child is now able to say that there is actually as much water in each of the vases. But if one makes her build, with cubes, a tower on a narrow surface, which has the same volume as a tower built on a larger surface, she realizes an approximate assembly with erroneous attempts of computations.

– From 11-12 years to 14 years, the child is in the stage of formal operations: she becomes able to reflect on moral and philosophical issues.

The child can build the tower of the previous example by precisely calculating the number of cubes needed to obtain the same volume.

Piaget’s observations were criticized because the child might not understand some of the questions because of a verbal immaturity, not a conceptual one. Experiments by Markman (1979), among others, show that children are able to recognize equalities of quantities despite different spatial arrangements, at an earlier age than that observed by Piaget.

Piaget also notes two distinct processes in learning: assimilation and accommodation. In the first case (assimilation), the subject interprets and retains the information coming from the environment, according to her/his existing knowledge. In the second case, accommodation, the subject questions his/her knowledge and therefore his/her future interpretations, according to the new information provided by the environment.

Accommodation implies a greater mental flexibility.

Existing knowledge thus influences the ability to acquire new knowledge: while respecting a principle of economy of effort, we are more permeable to the acquisition of information that is consistent with what we already know, rather than changing certain beliefs to take account new information.

This phenomenon helps to explain the persistence of prejudices or obsolete academic knowledge by schools and other institutions.

This also explains why we feel that we learn less in adulthood. As a child, the need to adapt in order to know how to survive is obvious. But when we have come to a relatively stable professional and familial situation, this need is less strong, so the natural tendency to minimize effort is prevalent, and we simply assimilate without questioning our patterns of thinking.

The ability to accommodate can however come back when the professional or familial situation is changed, or when we need to adapt to a foreign culture and its language, when we fall in love and we want to make the relationship work, or when we have a special motivation to learn something totally new.

Effect of education on genders

When the baby is born, its nervous system is not very developed. It will grow rapidly according to the first experiences that are presented to him.

Here is an extract of a book published in 1996 in USA “Hilgard’s introduction to psychology” (12th edition) by Rita L. and Richard C. Atkinson, Edward E. Smith, Daryl J. Bem and Susan Nolen- Hoeksema:

Observations made in the home of preschool children have found that parents reward their daughters for dressing up, dancing, playing with dolls, or simply following them around but criticize them for manipulating objects, running, climbing and jumping. In contrast, parents reward their sons for playing with blocks but criticize them for playing with dolls, asking for help, or even volunteering to be helpful (Fagot, 1978). Parents tend to demand more independence of boys and to have higher expectations of them. They also respond less quickly to boys’ request for help and focus less on the interpersonal aspects of a task. And finally, parents punishes boys both verbally and physically more often than girls (Maccoby et Jacklin, 1974).

Some have suggested that in reacting differently to boys and girls, parents may not be imposing their own stereotypes on them but simply reacting to real innate differences between the behaviors of the two sexes (Maccoby, 1980). (…) But adults approach children with stereotyped expectations that lead them to treat boys and girls differently. For example, adults viewing newborn infants through the window of an hospital nursery believe they can detect sex differences. Infants thought to be boys are described as robust, strong and large featured; identical looking infants thought to be girls are described as delicate, fine featured and “soft” (Luria & Rubin, 1974). In one study, college students viewed a videotape of a 9-month-old infant showing a strong but ambiguous emotional reaction to a jack-in-the-box. The reaction was more often labeled as “anger” when the child was thought to be a boy, and “fear” when the same infant was thought to be a girl (Condry & Condry, 1976). When an infant was called David in another study, “he” was actually treated more roughly by subjects than when the same infant was called Lisa (Bern, Martina & Watson, 1976).

Fathers appear to be more concerned with sex-typed behaviors than mothers, particularly with their sons. They tend to react more negatively than mothers (interfering with the child’s play or expressing disapproval) when their sons play with “feminine” toys. Fathers are less concerned when their daughters engage in “masculine” play, but they still show more disapproval than mothers do (Langlois & Downs, 1980).

But if parents and other adults treat children in sex-stereotyped ways, children themselves are the real “sexists”. Peers enforce sex-stereotyping much more severely than parents. Indeed, parents who consciously seek to raise their children without the traditional sex-role stereotypes – by encouraging the child to engage in a wide range of activities without labeling any activity as masculine or feminine or by playing nontraditional roles within the home – are often dismayed to find their efforts undermined by peer pressure. Boys, in particular, criticize other boys when they see them engaged in “girls” activities. They are quick to call another boy a sissy if he plays with dolls, cries when he’s hurt, or shows tender concern toward another child in distress. In contrast, girls seem not to object to other girls playing with “boys” toys or engaging in masculine activities (Longlois & Down, 1980).

This points up a general phenomenon: the taboos in our culture against feminine behavior for boys are stronger than those against masculine behavior in girls. Four and five years old boys are more likely to experiment with feminine toys and activities (such as dolls, a lipstick and mirror, hair ribbons) when no one is watching than when an adult or another boy is present (Kobasigawa, Arakaki & Awiguni, 1966; Hartup & Moore, 1963).

“Le Monde Diplomatique” presents a series of studies published in the issue “Femmes, le mal genre?”(“Women, the bad gender?”) From the collection “Manière de voir” (“Way of seeing”), March-April 1999. An article by Ingrid Carlander “An irrational fear of science” (“Une peur irraisonnée des sciences”), reports hidden camera observations that reveal that science teachers spend around 20% more time with boys. Girls are less questioned and are more frequently interrupted. Teachers encourage girls for their good behavior and the cleanliness of their copy, and boys for the relevance of their arguments.

Other observations performed in schools, reported by Aebischer in 1991, shows that teachers are asking for more participation to boys than girls (Guibert, 1987; Valabrègue, 1989), rely more on them in science and technology (Marques, 1990), talk more to them (Milner, 1989) and show more interest in what they do.