Screens are television, computer, smartphone or tablet, game console. Watching screens has become a common hobby, a companion, and, for families, a nanny. However, this leisure is not without danger for the cognitive development of children. Furthermore, it increases prejudices, aggressiveness and pathogenic consumptions.

Intellectual disabilities

Screens take the time that children could spend reading or acting on their environment, manipulating, inventing stories, looking for small animals or flowers, interacting with peers …

Most of the time, screens are watched in a passive way (online videos, television …). But movement is at the root of neuronal development. The most primitive forms of nervous systems are dedicated to the movement of a multicellular organism.

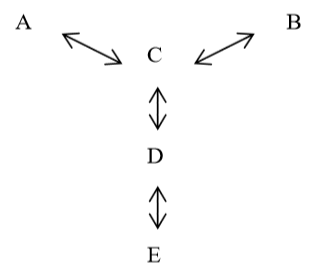

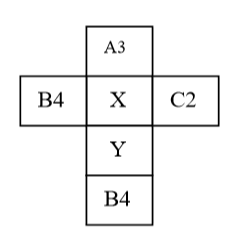

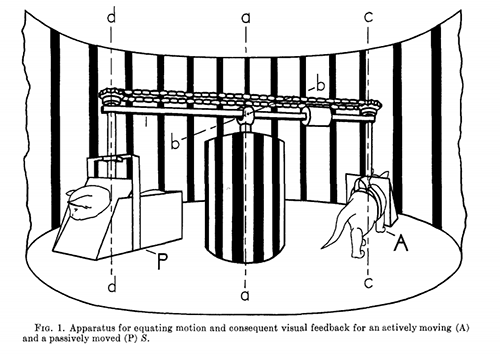

The experience of Richard Held and Alan Hein (1963) illustrates the importance of action in learning. They kept kittens in total darkness from birth. As soon as they became able to walk, they were exposed to light for 3 hours a day, during which, half of the kittens, always the same, could move by pulling each a small basket in which was another kitten. The other half of the kittens were those who remained passively in the basket. They could only move their head and see their surroundings. After a few weeks, active kittens had developed normal motor skills, while passive kittens behaved like blind kittens.

Source: https://marom.net.technion.ac.il/files/2016/07/Held-1963.pdf

Passivity itself is not bad, if it is properly balanced with moments of action.

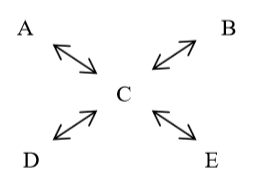

To act on the world, one needs to observe. Perception, reflection and action feed each others. It’s like a breath. Perception is an inspiration, action, an exhalation, sometimes taking the form of an intellectual action, we think about planning an action, a creation. And it is this need for action / creation that arouses perception and reflection.

But the perception of images on a screen is not a perception guided by ourself, for actions or future creations. It is a transformed flow of information, a rapid succession of images and sounds, designed to capture attention and sell. It hypnotizes, rather than informing.

Studies by Ayelet N. Landau, Michael Esterman, Lynn C. Robertson, Shlomo Bentin, and William Prinzmetal show that this form of attention involves different nerve circuits than those used in concentration on a task. It is called “automatic” or “exogenous”, as opposed to “voluntary” or “endogenous” attention. An experiment by Ayelet N. Landau, Deena Elwan, Sarah Holtz and William Prinzmetal shows that impulsiveness is correlated with the first form of attention (involuntary) and negatively correlated with the second form (voluntary). Television promotes the development of involuntary attention to the detriment of voluntary attention.

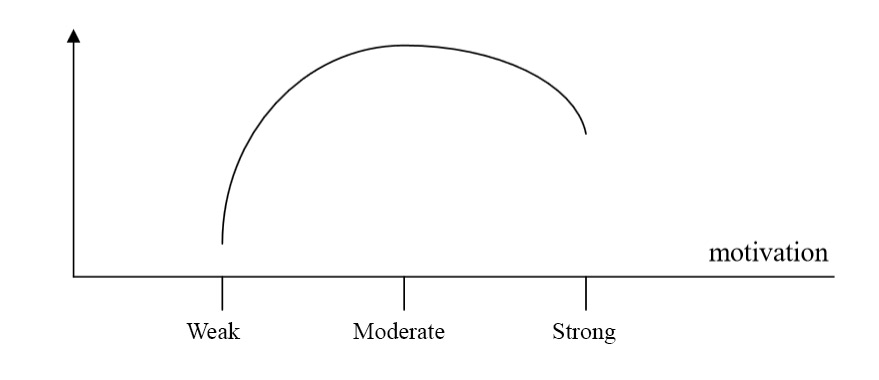

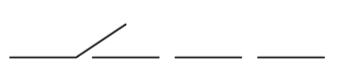

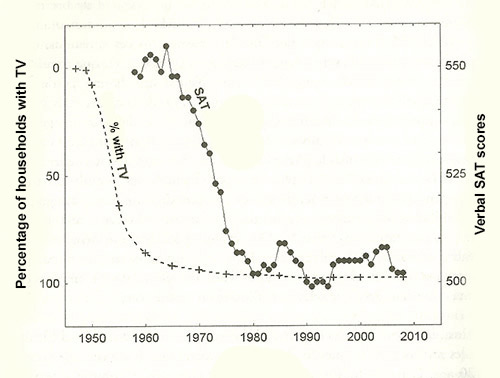

Michel Desmurget, in his book “TV lobotomy” (2011) quotes the study of Marie Winn which notes the collapse of performance between the years 1965 and 1980 on a test of verbal skills called verbal SAT, which is part of the selection tests used by American universities. She notes, in her book “The plug-in drug”, that this collapse is consecutive to the penetration of television in American homes, as indicated by the curve below:

We can see that the time between the two curves (number of households equipped and verbal SAT scores) is simply the age that students must have when they take the test.

That said, a correlation between two events does not necessarily mean that one is the cause of the other. A more prominent study is the one conducted by Tannis MacBeth Williams and her colleagues in the 1970s in Canada, and reported in her book “The Impact of Television: A Natural Experiment in Three Communities”.

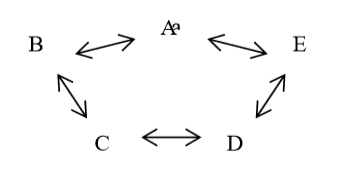

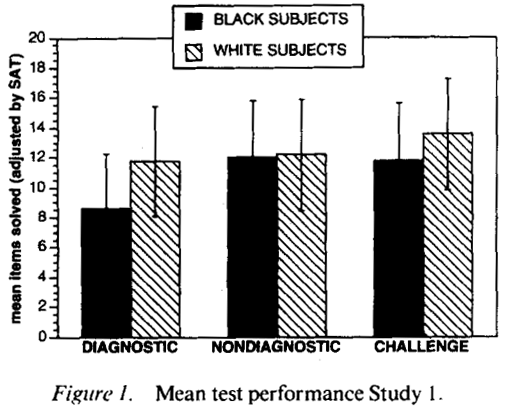

At the beginning of her study, not all Canadian cities have yet been connected to the TV network. Of those that are, some receive multiple channels, and others only receive one. This allows Tannis MacBeth to make three groups of children: NoTel (no TV), OneTel (a single TV channel) and multiTel (multiple channels). She measures their performance at a reading task. She notes that the results of the NoTel group are higher than those of the two others.

Shortly after, the municipality of the group NoTel is connected to the television.

Verbal performance is measured again two years later. The group of children of former NoTel maintains its lead over the other two groups. But this is not the case of new children of former NoTel belonging to the class level of children NoTel two years earlier, ie those who had access to television programs due to the connection. For these new children, there is no significant difference between the three municipalities.

Tannis MacBeth doesn’t only observe the damaging effect of TV on verbal performance. She also notes that television exposure increases aggression, gender prejudices, and reduces creativity.

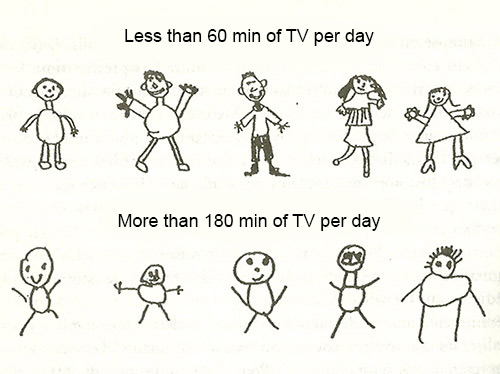

Studies reported in Carolyn N. Hedley, Patricia Antonacci and Mitchell Rabinowitz’s book “Thinking and Literacy- The Mind at Work” focus on hundreds of thousands of children, and find that their performance is negatively correlated with their television consumption.

Perhaps the impact of screens depends on the quality of the programs offered, and educational programs can be beneficial for children?

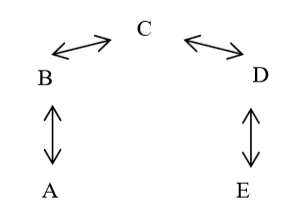

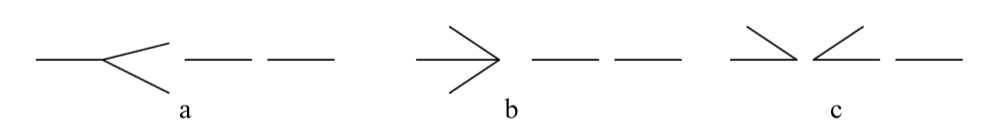

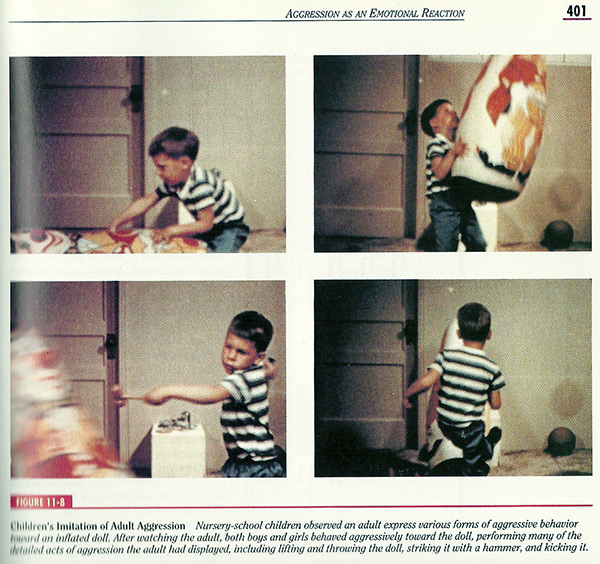

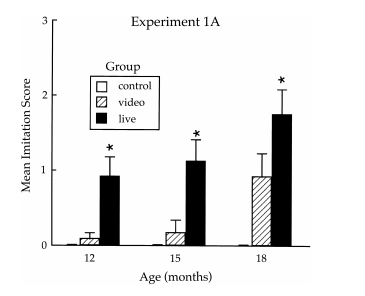

According to a study by Rachel Barr and Harlene Hayne, this is not always the case, at least for young children. In one of the experiments of their study, a woman shakes a puppet in front of children of 12, 15 and 18 months. She removes the bell that the puppet has in her glove, shakes it, then puts it back in the glove of the puppet. Some of these children see the woman in real life, the other sees a video recording. The results show an imitation rate of the complete demonstration much higher in the real condition, as shown in the figure below:

These results are consistent with those obtained by Cordua, Mac Graw and Drabman, 1979 (See “Role models”)

Violence

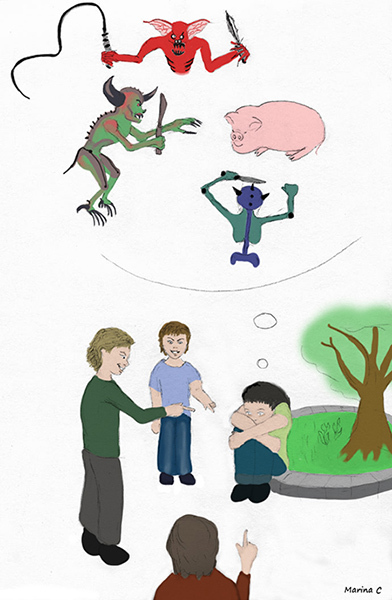

Does violence on screens influence children’s agressivity? The question is important because violent images are in constant increase. In the US, for example, we observe an average of 18.6 violent events per hour of cartoons on Saturday morning children’s programs in 1980, and it becomes 26.4 in 1990 (New York Times, 1990).

The American study “National Television Violence Study” (J. Federman, S. Smith, C. Whitney, J. Cantor and A. Nathanson, 1998), observed over 3 years 10 000 hours of randomly selected programs on 23 popular American channels. The results show that 60% of the broadcasts contained acts of violence, that they occur on average 6 times per hour, that they are perpetuated in a realistic way and positive characters. In more than 7 out of 10 cases, the violence caused no remorse, criticism or punishment. Another American study that shows that 70% of youth programs included violent content, with 14 incidents per hour (Barbara J. Wilson, Stacy L. Smith, James Potter, Dale Kunkel, Daniel Linz, Carolyn M. “Violence in Children’s Television Programming: Assessing the Risks”, 2002).

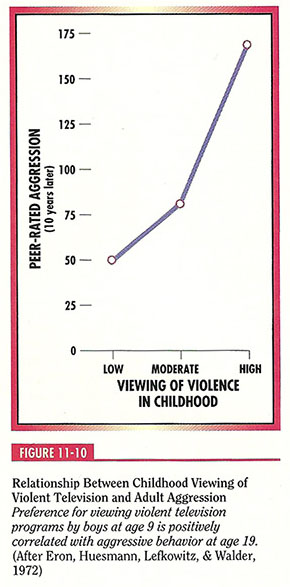

Eron, Huesmann, Lefkowitz and Walder, in 1972, conducted a study during 10 years. They noted the viewing habits of 800 children who are, in the beginning, 8-9 years. Researchers noted also their aggressive behavior, as reported by their classmates. Boys who watch a lot of violence are much more aggressive than those who prefer less violent programs.

Ten years later, half of these children were tested again on their television preferences and their aggressive tendencies, also reported by their environment. Results show that a high level of exposure to violence on TV at the age of 9 was positively correlated with aggressiveness at 19 years old.

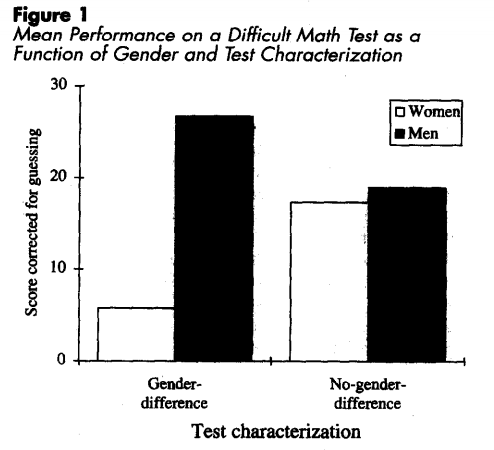

The study does not show a correlation for the girls, but most violent models on TV are male.

This experiment was confirmed by 28 others of the same type.

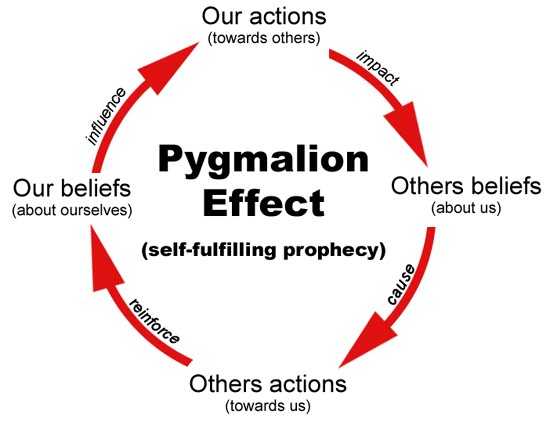

However, we can think that it was the initial aggressiveness of the child that orients him to violent programs. Other studies show that the display of violent programs precedes the appearance of aggressive behaviors in children.

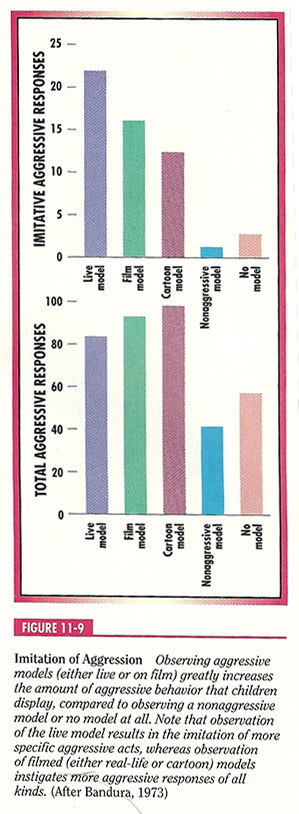

Michel Desmurget, in his book “TV lobotomie” (2011, in French) quotes a study by Kaj Björqvist made in 1985. He shows a violent video to a group of children aged 5-6, and a neutral video to another group of children of the same age. He observes the children’s behavior in the playroom after the video. The results show that children who watched the violent video were significantly more likely to push, hit, and provoke their peers than those who watched the neutral video. Similar results are reported on a study by Wendy Josephson (1987) who observes children 7-8 years old playing hockey after watching a video either neutral or violent. Michel Desmurget cites many other studies with similar results (“TV lobotomy”, pp. 219-221).

Mediated violence also affects compassion, through the phenomenon of habituation (described in the article “Active learning”). Michel Desmurget reports numerous studies. In one of them, conducted by Margaret Thomas in 1977, 8-10 children and college students are divided into two groups, one watching a violent movie, the other a non-violent movie. Then, the subjects are invited to watch the video of a real aggression. During the vision of this last video, the experimenters collect physiological markers of emotion (blood pressure, electrodermal response). The results show that these signals are strongly attenuated among the subjects who observed the violent film.

Michel Desmurget also cites studies showing that men exposed to violent images tend to accept more easily physical and moral violence against women (“TV lobotomie”, pp. 226-227). For example, he describes the study by Charles Mullin and Daniel Linz, in 1995, where faculty students were exposed to a horror movie every other day for six days. These contained a particularly heavy load of sadistic violence directed against women. Three days after the last screening, the students were exposed to videos in which women, victims of real violent assaults, described in detail her ordeal. The results showed that, compared to a control group that did not watch the horror movies, the students who viewed the movies felt less empathy for the victims, who were portrayed as responsible for their misfortune, and the severity their trauma was greatly minimized.

Take educated individuals, submit them to violent images involving sadistic behaviors directed against a woman, and our merry boys will eventually explain without blushing that rape victims are sluts who have desserved what happened to them and that anyway, it’s really not that bad.

(Michel Desmurget “TV lobotomie”, p. 227)

These results are the opposite of theories considering mediated violence as a cathartic outlet, and aggression as an innate need whose quantity and expression would depend on the genetic program specific to each individual.

The imitation of violence has tragic consequences in the area of sex. Sex education of adolescents is often done through the viewing of pornographic movies, made widely available through Internet. In pornography, however, pleasure arises mainly from the humiliation and enslavement of women. Girls learn, with more or less success, to find pleasure in these performances, to please their partner. It is difficult to measure how much this phenomenon alienates young people’s ability to establish a true loving, tender and empathetic relationship, and to get from this connection a more fulfilling and lasting form of desire.

One may also question the relationship between exposure to pornography and a greater risk to commit rape. We have already cited the studies reported by Michel Desmurget on the effect of watching horror films on the reduction of empathy toward women victims of violence. For some men and boys, visual models can even erase the line between fantasy and reality.

However, it is difficult to conduct rigorous experiments in this area, which would involve putting women’s safety at risk for the needs of an experiment. Studies are therefore most often based on the collection of interviews.

The study “Pornography and Sexual Violence” by Robert Jensen and Debbie Okrina, describes interviews that were conducted by Diana Russell (1998), and by Robert Jensen (2004).

Based both on the lab research and interviews, Diana Russell has argued that pornography is a causal factor in the way that it can:

(1) predispose some males to desire rape or intensify this desire;

(2) undermine some males’ internal inhibitions against acting out rape desires;

(3) undermine some males’ social inhibitions against acting out rape desires;

(4) undermine some potential victims’ abilities to avoid or resist rape

(Russell, 1998, p. 121)

Robert Jensen conducted interviews with pornography users and sex offenders, and various other researchers’ work. They have led him to conclude that pornography can:

(1) be an important factor in shaping a male-dominant view of sexuality;

(2) be used to initiate victims and break down their resistance to unwanted sexual activity;

(3) contribute to a user’s difficulty in separating sexual fantasy and reality;

(4) provide a training manual for abusers

(Dines & Jensen, 2004)

Here are some of the reports of these two studies:

From a woman involved in street prostitution, who reported that when one John exploded at her he said: “I know all about you bitches, you’re no different; you’re like all of them. I seen it in all the movies. You love being beaten. [He then began punching the victim violently.] I just seen it again in that flick. He beat the shit out of her while he raped her and she told him she loved it; you know you love it; tell me you love it” (Silbert & Pines, 1984, p. 864).

From a woman, interviewed in a study of sexual assault: “My husband enjoys pornographic movies. He tries to get me to do things he finds exciting in movies. They include twosomes and threesomes. I always refuse. Also, I was always upset with his ideas about putting objects in my vagina, until I learned this is not as deviant as I used to think. He used to force me or put whatever he enjoyed into me” (Russell, 1980, p. 226).

From a 34-year-old man who has raped women and sexually abused girls: “There was a lot of oral sex that I wanted her to perform on me. There were, like, ways that would entice it in the movies, and I tried to use that on her, and it wouldn’t work. Sometimes I’d get frustrated, and that’s when I started hitting her. … I used a lot of force, a lot of direct demands, that in the movies women would just cooperate. And I would demand stuff from her. And if she didn’t, I’d start slapping her around” (p. 124).

Other consequences

Michel Desmurget shows that television has also effects on sleep, eating disorders, excessive alcohol consumption and smoking.

The effect of television on pathogenic consumption reveals the damage of an economy based on mass consumption.

Television is becoming increasingly financially supported by advertising, which makes viewers “super-consumers”, with more damages on children. This closes the vicious circle of an economic system which ultimate outcome is the destruction of nature.

Modern lifestyle favors high television consumption: car traffic and crimes encourage parents to keep children safe at home, with their smartphone, computer, console, games and television. Work and travel times reduce parents’ time, attention and patience. Finally, in many households, fathers do not assume, or not enough, the parental and household duties that should be their’s as much as the mother’s, when she also works.